The human condition & the enduring value of content knowledge.

There is a fairly old argument being rekindled due to the exciting development of Artificial Intelligence. In the past, a case for change involved encyclopedias, then Google, then Wikipedia and YouTube… Now the message goes something like this: with the introduction of AI technologies like ChatGPT, all the world’s knowledge is at our fingertips. Thus, we no longer need to teach our young people content knowledge, rather, we need experts in thinking—Critical and Creative Thinking. Apparently, because individuals have access to unlimited information, we ought to require students to spend most of the school day learning “future proof” generic thinking skills. In this model of learning, students can ask generative AI for the information they require and then concentrate on the critical and creative thinking necessary for the twenty-first century.

For at least two decades, futurists have been telling us that AI is coming for “lower-order thinking” jobs. However, with the introduction of Large Language Models (LLM) and incredible Text-to-Image generators, it seems that the top of Bloom’s Taxonomy is being attacked quicker than first thought. Many blue collar workers are still very much untouchable with this iteration of technology revolution, whereas, it seems that knowledge workers and those in creative industries are the ones who may be most vulnerable.

Unfortunately, the evangelists calling for this worn-out message have ignored current research regarding cognitive architecture. The argument is tiresome because those who keep beating this drum neglect the fact that human cognition has not changed despite the exponential change we have seen in technology over the past century. And even though the next twelve months potentially will see us moving into an even steeper “S-curve”, unfortunately, the human brain does not work as conveniently as the revolutionaries would have us believe. We cannot simply tap into AI technologies and then use our “human-only” critical and creative thinking skills to become overnight experts. The hard truth is learning still takes time. AI is certainly going to help us learn more efficiently and effectively; however, if we want our young people to respond to this ever-changing world, we cannot give up on content knowledge to excessively emphasise generic thinking skills.

Relevant, content-rich schema stored in long term memory supports the significant cognitive bottleneck we have as humans (Sweller et al., 2011). Our working memory has the ability to retain novel information in the short term while simultaneously processing other information; however, there are consequential limitations (Goldstein & Naglieri, 2013). Working Memory can approximately hold between four to seven individual items at one time, but realistically the smaller amount (Cowan, 2001). The duration is also limited, with novel information only being held in working memory for approximately no more than a few seconds (Peterson & Peterson, 1959). In contrast, when information is processed from long-term memory, there are no known limits in both capacity and duration (Ericsson & Kintsch, 1995). Think of the cognitive effort between trying to desperately remember a phone number we have just heard left on our message bank; compared to how easily we can parrot our own mobile number when trying to get a discount at a member’s sale at Dan Murphy’s. One attempt is relying on our working memory, the other uses long term memory.

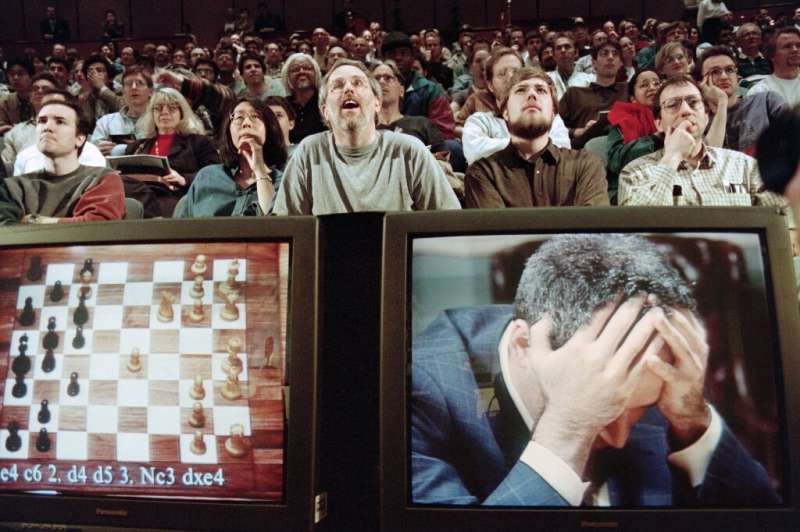

A fascinating study on chess grandmasters illustrates this important difference. De Groot (1965) took both grandmasters and casual players and showed them a series of chess configurations for five seconds. He then asked them to recall the positions of the chess pieces. The grandmasters demonstrated vastly superior recall ability compared to novice players. It was first thought that grandmasters had superhuman photographic memories. However, when the chess pieces were spread across the board at random, the grandmasters lost their edge, showing the same limitations of working memory as the casual players. De Groot’s study found that grandmasters were not expert problem solvers or strategists, as they shared similar thinking routines with casual players in their decision making. What made the difference was that grandmasters had memorised thousands of board configurations and their subsequent successful moves into their long-term memory as schemas that could be quickly recalled (Chase & Simon, 1973). The findings of this study have been replicated many times and in various domains (Ericsson & Kintsch, 1995).

How does this relate to thinking and learning? Novices have to rely on generic thinking skills; while experts use their vast knowledge stored in their long-term memory to turbo charge their cognitive ability (Sweller et al, 2011). When examining human cognitive architecture, we find that, ironically, the more domain knowledge we possess, the more we can actually use critical and creative thinking skills. If we rely on using problem-solving skills without drawing upon relevant domain-specific schema from our long-term memory, we are constantly going to think like novices and be disadvantaged (Kirschner, Sweller & Clark, 2006).

Wait a minute! AI was able to beat humans at chess decades ago; doesn’t that mean learning all those chess moves is a waste of time? Hence, learning anything that AI can do more effectively is also a waste of time?

Garry Kasparov, the famous chess grandmaster, was one of the first “knowledge workers” to experience this AI-induced existential crisis when IBM’s Deep Blue famously beat him in 1997. Many, at the time, were quoted as saying that chess would dramatically lose its appeal after his defeat. Surprisingly, though, that did not happen. If you walk into any school library at lunch time, some of our brightest young minds are still enjoying this cognitively challenging game. Furthermore, humans still enjoy watching other humans play chess, whereas there isn’t a huge appetite for AI vs AI chess tournaments. In fact, Kasparov actually attributes AI as a contributing factor for why chess is more popular than ever.

Takeaway points:

- Despite the dizzying speed of technological advancements, our cognitive constraints have not advanced. Our working memory is still significantly limited. It won’t be long until AI may help optimise how individuals can learn new information more efficiently than ever before. However, until AI can connect directly to our brain stem, Matrix-style, human expertise is still going to take longer than the educational revolutionaries would have us believe. Daisy Christodoulou reminds us that “if we want students to have advanced skills, they cannot leapfrog fundamental skills” (Christodoulou, 2023). F-12 schooling ought to continue building a strong, knowledge-rich foundation for our young people.

- Humans will continue doing things that are meaningful to them, despite technology being objectively superior across the domain. Just as humans kept riding bicycles after the invention of the motorcycle, humans are still going to want to paint, tell engaging stories, sing tunes, and think about complex and important issues. For humans to be successful in these pursuits, they will still need to put in the hard work and deliberate practice required for understanding something new and building expertise. For a beautiful defense of a knowledge-rich, or what he prefers, “an understanding-rich curriculum”, I encourage you to engage with the CEO of ACARA, David de Carvalho’s thinking on the matter.

- AI will help us learn more efficiently. This emerging intelligence is obviously going to continue becoming a powerful tool for humans to wield (as long as “it” lets us). Thus, schools shouldn’t just teach their students interesting and important content knowledge and skills from traditional disciplines (despite the inherent value of this knowledge). The most effective schools over the next decade will also support their students in learning how to leverage AI technologies both in the learning process and to accomplish great things.

Reference List:

Chase, W., & Simon, H. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, 4(1), 55-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(73)90004-2

Christodoulou, D. (2023, February 5). If we are setting assessments that a robot can complete, what does that say about our assessments? Retrieved May 6, 2023, from https://substack.nomoremarking.com/p/if-we-are-setting-assessments-that-a-robot-can-complete-what-does-that-say-about-our-assessments-cbc1871f502

Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 24(1), 87-185.

De Groot, A. (1965). Thought and choice in chess. The Hague : Mouton.

Ericsson, K. A., & Kintsch, W. (1995). Long-Term Working Memory. Psychological Review, 102(2), 211-45.

Goldstein, S., & Naglieri, J. A. (2013). Handbook of Executive Functioning (pp. 1–567). Springer.

Kirschner, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. (2006). Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Peterson, L. R., & Peterson, M. J. (1959). Short-term retention of individual verbal items. Journal Of Experimental Psychology, 58, 193-198.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. New York: Springer.

Leave a comment