AI and the current normlessness in education.

Just before the dawn of the 20th century, French sociologist Émile Durkheim described a concept he coined “anomie”, describing a state of normlessness. He observed that rapid social change, especially during times of economic or technological upheaval, often caused a condition of instability resulting from a breakdown of standards and values, leading to a sense of disconnection and purposelessness.

Education is currently in a state of “anomie”. An anomic state.

How did we get here?

It is easy to argue that since ChatGPT managed to gain 1 million users in the first 5 days and 100 million users after the first couple of months, education has been in a state of upheaval. Is the academic essay dead? If AI can outperform humans in everything we have traditionally taught our students, is there any point in teaching those things anymore? When our younger students graduate from school over the next decade, will they be competing in a workforce dominated by advanced Artificial Intelligence? How can schools possibly prepare young people for this potential reality? Many educators and social commentators are predicting a total disruption of the education system.

COVID-19

However, I sense an estrangement from previous norms and values actually started well before Generative AI. Instability was felt amongst the education system from the social fallout during COVID-19 lockdowns. Recently I was reading a discussion focused on the function of schooling amongst anonymous teachers on the subreddit r/AustralianTeachers. Multitudes of despondent educators admitted the schooling system’s primary function was to provide mass childcare for society.

After school teachers across the world were obligated to become “frontline workers” during Covid lockdowns so the economy could keep running, many teachers felt used and abused by political decision makers. This view was passionately expressed by a NY Times opinion writer when he critiqued the modern schooling system, titled: School is for wasting time and money.

However, my view is that the instability educators are feeling, both from ChatGPT and the sour aftertaste from COVID-19 lockdowns, are actually symptoms of a much older upheaval of the education system. The anomic state of education, the normlessness we are all starting to feel, isn’t the fault of Generative AI, it stems back to a radical change of direction education took in the later half of the 20th century.

The real villain: neoliberalism

I broadly blame neoliberalism for sucking the purpose out of education, not Artificial Intelligence.

With the introduction of neoliberal ideology in the 1980’s, the worst parts of capitalism were leveraged. Maximum production and consumption are the unquestionable goals of those in powerful positions across the Western world and this introduced market-driven approaches to many sectors of society untouched by the capitalist spirit, including education.

These policies tend to prioritise measurable outcomes, economic competitiveness, and efficiency for the sake of profit saving. With this market-driven approach, education became a means to an end: paid work for the individual and GDP for the economy. This instrumentalist view of school at its worse turns our students into mere commodities for a capitalist society. The younger Karl Marx, when critiquing the worst parts of capitalism, exclaimed, “[Capitalist] production does not only produce man as a commodity, the human commodity… it produces him as a mentally and physically dehumanised being” (Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts).

I don’t think anyone in the current education system is aiming to dehumanise our students, however, the constant focus on future work is actually a constant focus on students becoming human commodities. When the purpose of education diverges from the best interests of its primary stakeholders—students—it risks aligning with external agendas. Such a shift can objectify and, consequently, dehumanise the individual.

This might sound somewhat familiar. Even before AI, people have been calling for an Education Revolution. Arguing that the “industrialised model of education” is outdated and is in urgent need of disrupting. When ChatGPT emerged on the scene last November, many educational revolutionaries welcomed this digital chatbot in a triumphal procession. They see AI as the great disruptor. Calling to throw out the old and replace with the new. The message now emphasises the preparation of students for the AI era. Because AI is disrupting the future workforce, many educators and policymakers are arguing that we ought to turn our efforts to prepare students for this AI infused world.

Pseudo-Revolution

My worry is that this revolutionary message, is in fact, neoliberalism in a different mask. We are still just preparing students for future work. Is this rally call really a revolution?

The critique of the 20th century industrial model of education has been a key theme at many educational conferences for the past two decades. For many years, the educational revolutionaries have been advocating that schools should move away from making students simply “regurgitate facts”. Schools should instead focus on “21st century skills”, such as critical thinking, creativity, communication and collaboration.

Jared Cooney Horvath highlights the etymology of these 21st century skills. He found the first group of people who met in the same room and started trying to define these “generic skills”. In 2002 in the US, a group of industry leaders and educators met together and called their endeavour, “The Partnership for 21st Century Skills”. The industry leaders were companies such as Microsoft, Apple and Dell.

These large, multinational technology companies were telling educators what graduate skills they should be teaching so future workers could adequately fulfill their industrial needs. Are we happy that our students are still cogs in a industrial focused machine? The machine looks different compared to the early 20th century, but people calling for education to be centered around 21st century skills are actually advocating for a 21st century industrial model instead.

A broader purpose

More than ever, we need a broader, richer purpose for education to guide us through the instability, the anomie, our profession is experiencing. This obviously needs to go beyond the the base idea of it simply fulfilling the childcare needs of the more “important” aspects of society.

I was incredibly encouraged to read David de Carvalho (CEO of ACARA – the organisation responsible for the Australian Curriculum) calling us back to an earlier understanding of what it means to be “educated”. He wondered if in the age of AI, we ought to spend more time focusing on helping students become active and informed citizens, rather than just workers; to help young people discover what it means to be human.

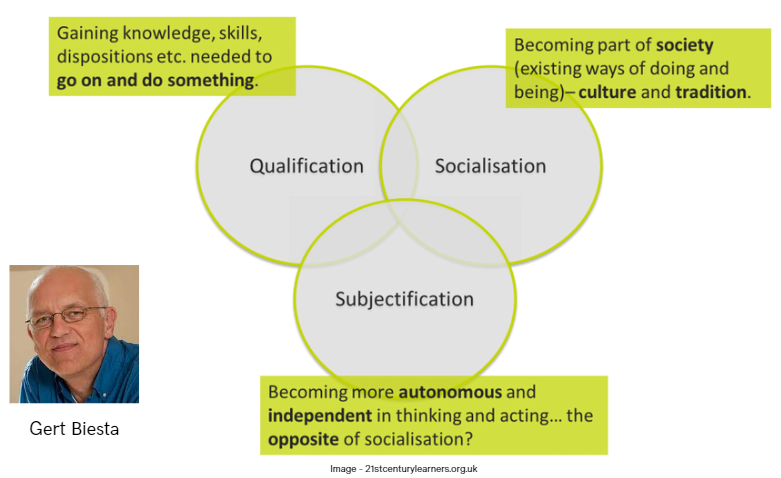

It reminds me of my favourite description of the purpose of education from the work of Gert Biesta. He explains that education’s purpose is actually multifaceted. He condenses its function down to three broad domains: Qualification, Subjectification and Socialisation.

Qualification

Education obviously should equip students to have the ability to proficiently do something. Despite my critique of the instrumentalist function earlier, it would be a position of privilege to suggest that education shouldn’t serve any utilitarian function. The problem came when neoliberalism narrowed the purpose of education by overshadowing the other two domains with its market-driven approach. However, we can frame qualification wider than just paid work. Students could use their qualifications to function within and contribute to society.

Socialisation

Education should also help students learn to live in community. Obviously by participating in group projects, team sports and unstructured play, students experience and develop firsthand the skills of teamwork, sharing, taking turns and conflict resolution. Australian schooling has usually been pretty good at this function. But socialisation ought to be broader than this. It also means preparing students to become democratic citizens. To understand the culture they are born into, but also other cultures they live alongside. A good education should help an individual become more empathetic. School can be a place to learn about history, including the problematic, the contested and the often forgotten histories.

Yuval Levin makes an interesting point when he suggests that society has “moved, roughly from thinking of institutions [such as schools and universities] as molds that shape people’s characters and habits, towards seeing them as platforms that allow people to be themselves and to display themselves before the wider world.” I believe this progressive move of culture has been a positive development, as some parts of the socialisation of old was not just repressive but often oppressive. The subversion of some power structures with the influence of postmodern thinking has been good for the individual. Especially vulnerable individuals from minority groups. However, have we gone too far? Has postmodern thinking also stripped away the idea that education can impart not just knowledge to our young people, but also wisdom. School ought to be a time young people can be encouraged to see the world as bigger than just their individualistic wants and interests, to broaden their horizons. School can be place where students are exposed to a knowledge-rich curriculum. A curriculum, to quote David de Carvalho, to help students experience things “they wouldn’t or couldn’t come to acquire without their attention being directed to them by their teachers”.

Subjectification

However, now to contradict myself. Education should empower student individuality. The socialisation and subjectification functions of education, despite being contradictory, should be held in a constant tension. School should be a place where an individual can come to realise they are the “subject” of their own life. Not the object for someone else’s needs. The OECD calls this idea student agency, which is about “acting rather than being acted upon; shaping rather than being shaped; and making responsible decisions and choices rather than accepting those determined by others”. An approach to education that promotes self-determination should be liberatory. It should be existential. Students can find themselves and their humanity.

When taken too far and isolated from Biesta’s other domains (especially socialisation), this emphasis can foster hyper-individualism. To find balance we can be influenced by Paulo Freire, the famous Brazilian educator and philosopher who advocated for an education that cultivates a “critical consciousness“. A type of critical thinking (different from the 21st century skill defined by the tech industry), that helps individuals become aware of oppressive, objectifying forces, often systemic in society. However, this critical consciousness is not just for the sake of the individual, but also for the sake of other oppressed communities.

Closing remarks

As we feel the angst of instability from the changing landscape of education, let us guard ourselves from narratives that narrow rather than broaden the purpose of the education.

Should schools prepare young people for an AI infused workforce? Yes.

Should this be the primary focus of education? No.

If we use Biesta’s framework to inform our educational goals, this should evoke a measured and balanced response even to an economy disrupting event like the significant advancement of Artificial Intelligence. Why? Because under this paradigm, the economy is not the only driving force of the educational system.

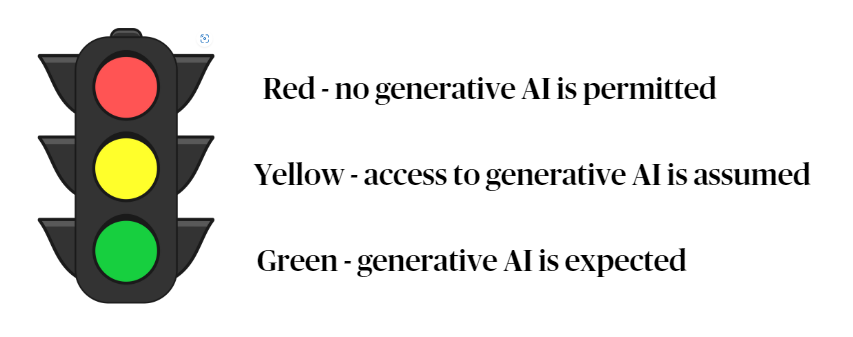

Does this mean we ignore AI? Certainly not.

I believe Generative AI, especially those based on Large Language Models (LLM), can offer much to our educational endeavour. However, it could also potentially compromise and complicate the tension between qualification, socialisation and subjectification.

Let us not be drawn to what Evgeny Morozov coined, “Technological Solutionism“. AI cannot solve all our problems. It is unlikely automation will save teachers significant amounts of time any time soon. If something can be truly automated without a human in the loop, it’s probably a task of very little educational impact. There is probably more promise in Generative AI’s potential ability to augment our abilities rather than automate them.

Ultimately, we need to emphasise our human students in our great act of education. We cannot succumb to the potentially dehumanising capitalist agenda, but we also can’t ignore the disruptive force this emerging technology will have on society. A rich and holistic educational purpose should guide and direct us through this anomic state.

Leave a comment