Critical Thinking is not Enough

Well before the arrival of generative AI, many voices have been advocating that the development of critical thinking should be a chief function of education. Most agree this endeavor is one of the key purposes of schooling in modern society. However, significant debate arises for how we can genuinely develop this type of thinking in our students. Can it be taught as a generic skill? Or is it developed alongside domain-specific expertise?

Cognitive Scientist, Daniel Willingham, argues that we can certainly teach specific critical thinking skills. This type of thinking is teachable. However, there is a significant caveat. Study after study shows humans are pretty terrible at transferring these critical thinking skills. Especially when the contexts are significantly different. Jared Cooney Horvath, neuroscientist and educator, convincingly explains this cognitive limitation here. When we teach critical thinking in one domain, it very rarely transfers successfully to another unrelated domain. An inconvenient reality is that critical thinking is not a generic skill that can be taught in isolation.

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Anyone interested in critical thinking, ought to consider reading an illuminating classic by the late cognitive psychologist, Daniel Kahneman: Thinking, Fast and Slow. A significant section of the volume details further inconvenient truths regarding human thinking.

System 1, System 2

Kahneman is famous for articulating a fairly well-documented feature of human cognition, which he calls System 1 and System 2.

System 1 thinking is fast, automatic and intuitive. It operates almost effortlessly without deliberate or conscious control. This system is responsible for our gut reactions and snap judgments. However, System 1 is often significantly influenced by cognitive biases, thus, can be prone to errors.

System 2 on the other hand is deliberate, effortful, and requires conscious mental effort and attention. System 2 is activated when System 1 cannot quickly come up with a plausible, intuitive solution. This system is usually engaged when we need to perform complex computations or engage in reasoning that demands focus.

best part of System 1: Expertise

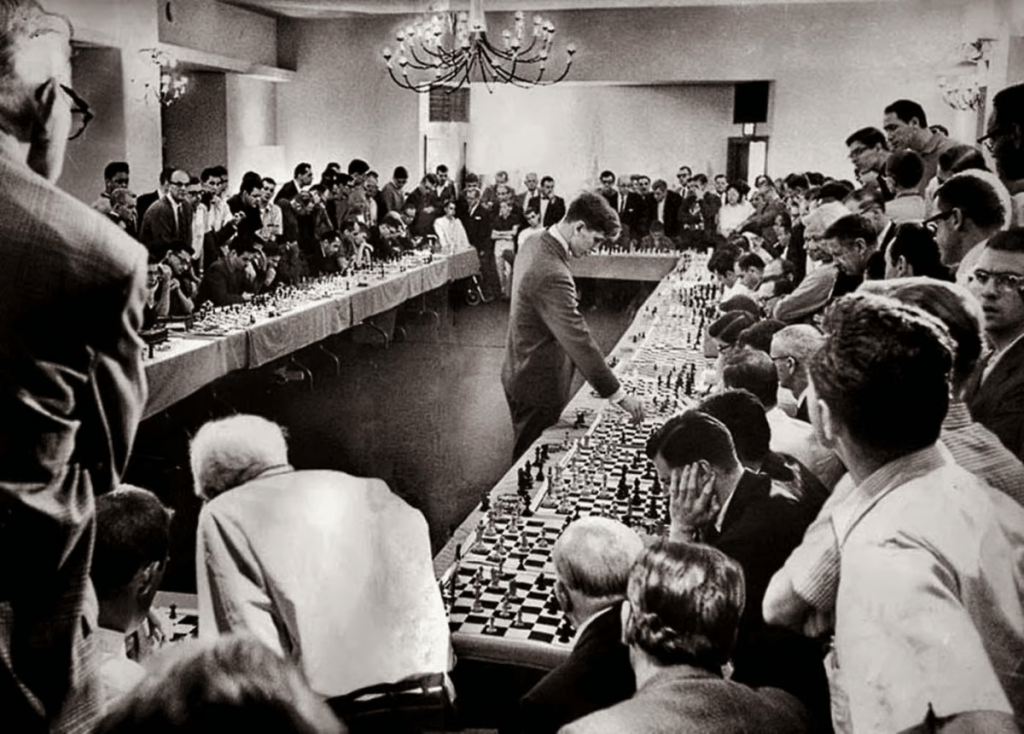

An expert’s ability to leverage their System 1 thinking across their domain of expertise can often look like a superpower. The chess grandmaster, Bobby Fisher once played 50 opponents simultaneously, he won 47 matches, drew 2 and lost 1. His ability to quickly and intuitively know the right moves to make at that speed and scale is a testament to domain expertise.

However, this feat was not due to Mr Fisher’s superior intellect or thinking skills. Rather, a chess master’s superior skill is due to thousands of board configurations, and possible successful moves for each configuration stored in their long-term memory.

To quote Kahneman, “expert intuition strikes us as magical, but it is not… the situation has provided a cue; this cue has given the expert access to information stored in memory, and the information provides the answer. Intuition is nothing more and nothing less than recognition” (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011, p.11).

We live most of our lives in System 1, which works fine most of the time. This is also why building expertise is important, especially if we want to make good choices. Because System 1 thinking is usually the culprit when human judgement fails. Which for most of us, happens more often than we would like to admit. And often, can happen without us even realising.

Worst Part of System 1: Cognitive Bias

Throughout the book, Daniel Kahneman outlines a series of cognitive biases that plague System 1 thinking. ChatGPT will give you a summary here.

Kahneman calls one of these biases the “What You See Is All There Is” (WYSIATI) effect. This cognitive bias often causes us to jump to conclusions based on the information that is immediately available to us, without considering what we might not know.

When we are outside of our domains of expertise, Kahneman reminds us of a bleak reality of the human condition: we have an “almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance” (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011, p.201).

Intuitively, it feels right…

For another example, here is a simple puzzle used by Kahneman.

Do not try to solve it but listen to your intuition:

A bat and ball cost $1.10.

The bat costs one dollar more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

What number came to mind? The obvious number is 10c right? That answer is “intuitive, appealing and wrong” (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011, p.44). If you do the maths, that answer would give a total cost of $1.20. The correct answer is five cents.

I hope you were not so easily fooled with this simple puzzle as I was. It made me feel better to read that a sample of more than 50% of Harvard, MIT and Princeton students gave the same incorrect answer.

So, what went wrong?

Your System 2 is lazy…

According to Kahneman, one of System 2’s main jobs is to “monitor and control thoughts and actions suggested by System 1, allowing some to be expressed directly… and suppressing or modifying others” (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011, p.44). However, for those of us who made the mistake, on this occasion, our System 2 thinking was too lazy to engage. It assumed our System 1’s first attempt was plausible enough not to get involved to critique the (now) so obvious wrong answer.

System 2 can and does override the impulses and intuitions of System 1. However, the second system is cognitively demanding. It requires a lot of mental energy. Thus, System 2 is often lazy, attempting to preserve cognitive energy by preferring to default to the easier and faster responses of System 1 when possible.

So, what has any of this to do with critical thinking or generative AI?

ChatGPT is not magic; it’s probability…

The more I learn about how tools such as ChatGPT work, the more I am amazed at what has emerged from the construction of Large Language Models. Here is a really helpful video explaining the power of probability behind Generative AI. However, I am also increasingly becoming more grounded in the current limitations of this technology. In this interview, Edward Gibson, a psycholinguist, helped me understand that tools like ChatGPT are extremely good at the surface form of language. Using the power of probability, we can all see that Generative AI can string words, sentences and paragraphs together to form seemingly intelligible language. However, technologies such as ChatGPT still do not understand the meaning behind the language. The chatbot is proficient in the language, but ignorant of the thinking behind what the language attempts to convey.

ChatGPT is missing System 2

We could assert that AI tools like ChatGPT, Claude and Gemini can successfully mimic the quick, intuitive System 1 thinking we humans possess. Using contextual cue recognition, the power of probability and their gigantic neural networks, this technology is seriously impressive at sounding like it has expertise in numerous domains.

However, unlike humans, Large Language Models lack anything resembling System 2 thinking. Even the current most powerful frontier model, GPT-4o, has no functionality to check if what it is generating is reasonable and true. Generative AI is completely missing this self-checking feature. What we have is an artificial intelligence that mimics System 1 thinking using nothing more than probability, but it also has no ability to understand when it could be incorrect. This is why these tools unknowingly ‘hallucinate’.

As the technology keeps advancing, we may see emergent traits from Large Language Models that start resembling human-level reasoning or System 2 functionality. However, because of the current lack of genuine understanding from the machine, generative AI has little grasp of reality. It does not comprehend when it’s generating something accurate; or when it’s actually generating plausibly sounding untruth. Generative AI’s ignorance is its greatest flaw.

A cocktail of ignorance

To bring these ideas together, I hope you can see that we have some serious ramifications for education. When a novice interacts with generative AI, we have an unfortunate reality:

What the novice reads from ChatGPT is language framed and formed convincingly detached from understanding and meaning. Additionally, the machine currently has no ability to understand if what it’s generating is accurate, or plausible sounding rubbish. Furthermore, the novice will likely have the tendency to succumb to the “What You See Is All There Is” effect. They don’t have the ability to ‘intuitively’ know what is accurate or what is rubbish. Without the required knowledge stored in long-term memory, the novice is ignorant for when they may need to use their ‘critical thinking skills’.

What we have is a cocktail of ignorance. Both in the machine and in the human.

Educators need to take these ramifications seriously. This is one of the biggest current challenges Generative AI brings to education.

Part 2: Embracing scepticism

Leave a comment